Lost in Translation

How English-Speaking Nigerian rappers lost the plot to indigenous rap music.

What happened to Naija Rap? Specifically, what happened to the English-speaking rappers in Nigeria?

The scarcity of English-speaking Nigerian rappers in the mainstream music scene today is not a conundrum. Why today’s English wordsmiths have been relegated ahead of indigenous rap, street hop and street pop is because of their neglect of an important constituency of rap music - the streets.

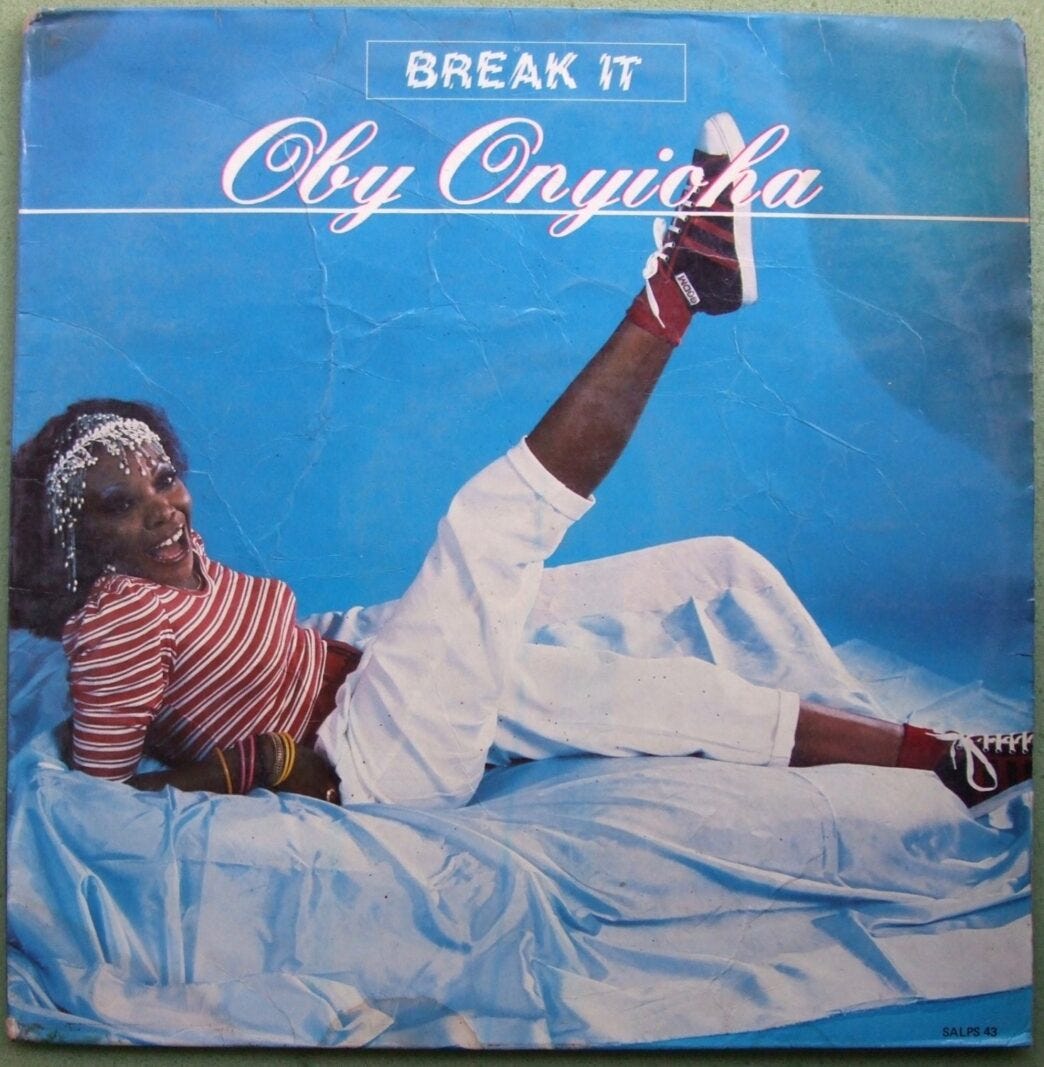

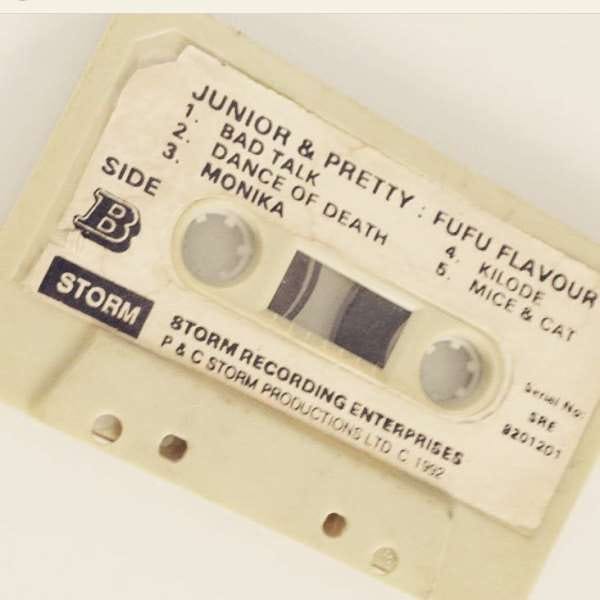

Take a walk with me. When rap music emerged in the 1980s in the country, it suffered from two things: credibility and talent. “For years, the earliest attempts at homegrown rap were ridiculed, resisted or downright reviled by the mainstream. And in some cases, perhaps, rightfully so: they were often awkward, overly imitative, fatuous,” wrote music historian Uchenna Ikonne in his article, Nigerian rap: the first decade (1981 – 1991) for African Hip-hop in 2009.

If you listen to most of the disco-rap records from the 1980s, you would rate them as amateurish and comical. The following decade would prove much better with Junior and Pretty setting the tone with their hit single ‘Monika’ and their debut album, Fufu Flavour, released in 1992.

Nigerian rap would claw its way to national attention thanks to the pioneering efforts of Weird MC, Zaaki Azzay, Baba Dee, Black Masqueradaz, Dr Fresh, Seyi Sodimu and others. Towards the end of the decade, Remedies’ seminal hit, ‘Sa Komo,’ regarded as the official coming-of-age for the Afrobeats generation, put a spotlight on rap, thanks to Eedris Abdulkareem and his scene-stealing aura.

Despite the strides of the music genre in the 1990s, it still lacked credibility among the cool kids, young Nigerians from strong middle-class and upper-class backgrounds. These were the kids who went abroad for vacation and had the big satellite dish installed in their homes. They attended posh private secondary schools or legacy ones like Atlantic Hall, A.D.R.A.O. International School, Corona Secondary School, Vivian Fowler, Avi-Cenna International School, British International, etc.

This class of kids served as gatekeepers of credibility and the social prefects of cool. They determined which songs or albums were cool enough to get spins in the class. If it didn’t sound like Nas or Snoop Dogg with the finicky production style of Dr Dre, your mixtape of Naija songs was getting tossed out of the class. Naija was not a cool concept in the 90s. Foreign aesthetics and tastes dictated youth culture, evidenced by the dominance of American urban records on the radio and Nollywood imitating Hip-Hop culture in youth-centric films.

These privileged youngsters turned their noses up at Nigerian rap records. The demand for lyrical proficiency and delivery led to the emergence of Trybesmen and SWAT ROOT, which heralded a decade-long era of coolness and credibility. LAG Style Vol. 1 by Trybesmen, Six Foot Plus, and Terry Tha Rapman’s debut albums (Millennium Buggin’ and Tha RapMan Begins) signalled a shift - albeit a violent one, as proven by Rugged Man taking Eedris Abdulkareem to the cleaners on ‘Ehen’ (circa 2002). This marked a shift in Nigerian Hip-Hop music as proficiency became essential in being perceived as a top MC.

The rise of M.I and Naeto C further entrenched Naija Rap among the middle- and upper-classes through their lifestyle-driven projects, Talk About It, and You Know My P.

The landmark rap albums, dating from 1999 to 2009, were the best of any era. On Modenine’s debut album, E Pluribus Unum (2007), the god emcee tackled heavy themes such as cultism, alcoholism, widows’ rights, political oppression and pan-Africanism. In earlier efforts, Modenine rapped about the poor state of Nigerian education and advance fee fraud. Talk About It (2008), M.I Abaga’s glorified classic debut album, made room for heavy subject matters, civil resistance and poverty.

Even with the conscious efforts of Nigerian rappers, the streets were ignored, with Street-hop version 1 acts, catering to them, such as Krazee Kulture, Artquake, Konga, etc. At this point in history, a sub-type of Nigerian rappers also served the streets - indigenous rappers.

English served as the undisputed lingua franca of Nigerian Hip-hop from its 1980s inception. The 1999–2009 era signalled a transition, as artists increasingly experimented with indigenous languages, breaking the monolinguistic mould of the previous decades.

By the year 2000, the movement was already gaining momentum as pioneers like London-based AY and Lord of Ajasa began making waves with their signature Yoruba-infused rap.

On Da Trybe’s posse jam, ‘Oya’, 2Shotz abandoned his usual English delivery for a more Igbocentric performance. In 2005, Mr Raw (f/ka/ Dat Nigga Raw) scored a major hit with ‘Obodo’ featuring Klint Da Drunk, a thorough Igbo rap record. And while Illbliss showed his white-collar Igbo sensibilities on ‘Dat Igbo Boy’ off his debut album of the same name, Naeto C and Ikechukwu were also offering an upscale, metropolitan version of his Igbo heritage.

As the movement’s early flagbearers, Mr Raw and Lord of Ajasa paved the way for a gritty, street-led revolution in the Nigerian rap scene.

The ‘streets’ means the impoverished, informal workers, hustlers, unemployed youths and the millions in slum communities. As Ruggedman rapped on ‘Peace or War,’ “I speak for shoe makers. I also speak for mechanics.”

The streets in rap music are the most powerful constituency. Hip-hop is the byproduct of neglect. It crawled out of the catacombs of The Bronx precisely because the marginalised and the forgotten needed a way to be heard.

In Hip-hop, in the streets are the ultimate tastemakers. They decide what becomes a movement, who becomes the anointed rapper and what a classic album is. It is the engine of the culture and the heart of the art form.

And while Nigerian rappers had hit singles and big albums that crossed over to this demographic, it didn’t accurately represent them. Middle-class or upper-class validation blinded many rappers to the reality of the Nigerian youth, hardship, unemployment, police harassment, and hopelessness. Well, that was until…

Dagrin’s Chief Executive Omota arrived in September 2009 with a definitive boom. In my review of the classic sophomore album, I said, “Dagrin’s usage of the Yoruba language to lucidly illustrate his pain, sorrow, and eventual victory in the game is as revolutionary as Rev. Samuel Ajayi Crowther translating the Good Book into Yoruba.”

CEO is the pivotal moment when indigenous rap and the streets crossed from the margins into credibility, respect, and mainstream success. It heralded the golden age for vernacular rappers whose bread and butter would be street representation. The album was a triumph for equity, a victory for the downtrodden and an affirmation that the streets are rap’s most important constituency and it wouldn’t be ignored again. And it never was.

From 2009 - 2019, indigenous rappers monopolised the rap music industry. Led by Olamide, Reminisce and Phyno, they took the mantle from the English-speaking rappers. Anthems like ‘Voice of the Streets’, ‘Alobam’ and ‘Local Rappers’ turned this trio into street gods, upending the rap hierarchy in the country. What endeared them to the mass audience was their representation of the streets, the impoverished, which swells daily in Nigeria and is now the most important demographic in Nigerian pop music, judging by the impact and the size of street pop and street hop in the last decade.

Not only do these genres articulate the pains and frustrations of a young generation, but they also amplify their contradictions and celebrate their victories. Across a decade-long reign, these indigenous heavyweights carved out a legacy as “street gods,” becoming the undisputed voices of the grassroots.

The brilliance of indigenous rappers who speak for the streets is that they also morphed into Street-hop acts and frequently collaborate with street-pop artistes, expanding the sphere of their influence.

The neglect of the impoverished, an underclass that held little value to English-speaking rappers, has come home to roost. With each passing year, English-speaking rappers struggle for relevance and cultural authority. Today, the streets reign supreme even though the cultural power of Yoruba rappers has dwindled.

This is not to say some rappers haven’t been able to find relevance. By blending sharp wit, seamless code-switching, and biting social activism, Falz has secured his position at the forefront of Nigerian Hip-hop royalty. Show Dem Camp used its cult following and extensive discography to scale into one of the biggest rap acts. Blaqbonez relied on Gen-Z aesthetics and the Internet’s trolling culture to emerge as a prominent rapper.

The closest we have to a full mainstream English-speaking rapper is Odumodublvck, who primarily raps in Pidgin English and is far from a favourite of the conservative rap bloc for his unabashed use of melodies, unconventional rhyme schemes and patterns.

Today, English-speaking rappers find themselves sidelined, struggling to maintain a foothold in a mainstream now governed by the streets. They remain far from a state I call Mass Locking.

Mass Locking describes the moment a rapper reaches the absolute peak of pop-culture saturation, where music, image, language, institutions, and public life align around them, granting definite mainstream dominance. Mass Locking differs from commercial success. It is the persistence of cultural presence regardless of release dates.

There are four levels to achieve Mass Locking. They are: the Street Mass, the Subcultural Mass, the Institutional Mass and the Elite Mass.

Note: ‘Mass’ in this essay is not in the sociological sense. It describes unique layers of cultural validation within contemporary pop music culture.

Street Mass - This refers to the grassroots audience who represent street culture. This is the streets. This level pays premium attention to rappers who reflect their daily experiences, use local languages or Pidgin English, and incorporate slang, humour, or local narratives into their music. Rappers who excel in this level are relatable, authentic, and culturally resonant. Success at this level often translates to high engagement in urban neighbourhoods, social media buzz, and viral street-level popularity, making it the foundation of cultural impact in Nigeria. Indigenous rappers thrive at this level. Note: the street is not morally pure, but it is culturally decisive.

Subcultural Mass - This level is for niche audiences, tastemakers, and early adopters within the music scene. This group prioritises technical skill, innovation, precision and originality. Innovation and experimentation are welcomed here. Successful rappers at this level achieve critical acclaim, recognition in underground platforms, and trend-setting influence. They find it difficult to translate critical acclaim to mainstream success. In the hierarchy of mass levels, subcultural mass is supplementary.

Institutional Mass - This refers to the network of media platforms, brands, award bodies, radio, streaming services, and other formal gatekeepers that influence what reaches the general public. Rappers who succeed at this level must possess visibility, consistency, and commercial appeal. This leads to chart dominance, playlist playments, brand endorsements and mass media coverage. This ensures continuous exposure and structural support. These media platforms tend to allocate time, coverage and resources to rappers who have cultural impact from a base level.

Elite Mass - This refers to an intelligentsia of cultural critics, journalists, academics, thought leaders, and socially influential audiences. These gatekeepers set standards of taste and validate cultural significance. They prioritise artistry, innovation, and the preservation of legacy. They respond most to artists whose work demonstrates intellectual, historical, and cultural relevance. Success at this level often translates to critical prestige and recognition in cultural discourse.

While all four Masses shape cultural influence, they do not function equally. Street Mass and Institutional Mass are foundational and inevitable. Subcultural and Elite Masses are supplementary, refining legitimacy, prestige, and legacy, particularly within niche and critical audiences.

It is rare for a rapper to excel in all four levels, but the best example is Olamide. The legendary rapper is a deity in the streets, a priority act at the institutional mass level, and after years of superhuman consistency has attained elite mass (even if begrudgingly by some part of the intelligentsia). The level at which he doesn’t excel is the subcultural level where Hip-hop heads are indifferent to him and what he has achieved for the genre. Although in the alte sub-community, Olamide is a respected figure.

At the peak of his pop-culture presence, M.I Abaga scored highly across all levels except the Street Mass. After the emergence of Dagrin, he briefly tweaked his albums, MI 2 and The Chairman, to accommodate the streets, but little came out of it. Overall, his dominance was institutional and elite-facing, not street-driven.

Many indigenous rappers usually score high in Street Mass and Institutional Mass. Most English-speaking rappers easily achieve Subcultural Mass and Elite Mass. However, since Street Mass forms the baseline of pop-cultural dominance, most indigenous rappers who maintain consistency eventually penetrate the Elite Mass level.

The flaw of many English-speaking rappers is that they want to achieve Mass Locking from the top down rather than the opposite, from the grass roots to the academic layer. Many bypass the streets, a fundamental error in gaining dominance. Not only is the Street Mass Level the first level, but it is the most important.

“We make music the way people actually want to consume it. People want to listen to rap in their own dialect. They want to recite rap lyrics in their own language,” said Reminisce in a 2013 Al-Jazeera feature article I wrote.

Language is access to culture. It is more than a medium of communication. It is where culture is created and stored. In Decolonising the Mind (1986), Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o contended that language is inseparable from the culture it embodies, transmitting values that shape how its speakers understand themselves and their place in the world.

Therefore, culture comes through language. Rap music, due to its origins, is primarily expressed in English, which was imposed by Anglophone colonialists on Africans. This made English synonymous with authority, legitimacy and power. It gave it dominance over local languages, which were marginalised and associated with inferiority or backwardness. This is the basis of Frantz Fanon’s book Black Skin, White Masks (1952).

This linguistic hierarchy influenced early Nigerian Hip-hop from the 1980s. Early Nigerian rappers absorbed the culture and its mastery of English to prove authenticity and alignment with international sophistication.

The messages and expressions of early Nigerian rappers were lost in translation because they couldn’t articulate local realities. Early Nigerian rap was devoid of proverbs, praise poetry, tonal humour, and moral idioms. Sociolinguist H. Samy Alim, in Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture, argues that rap’s authenticity is rooted in localised linguistic practices that emerge from particular speech communities. He suggests that as linguistic and social distance from these communities increases, claims to cultural authenticity become more unstable.

In simple terms, JAY-Z’s Brooklyn accent, T.I.’s slurred Atlanta delivery, and Kendrick Lamar’s Compton-inflected intonation grounded them in their communities before they rose to global superstardom. Rapping in linguistic styles alien to their stomping grounds wouldn’t have given cultural legitimacy. Hence, we can now deduce that many English-speaking rappers struggle to break through to a street culture where indigenous languages and Pidgin English are the chosen means of communication.

Am I advocating English-speaking rappers abandon our lingua franca for their mother tongues? No. What I suggest is that they study how 1990s Nollywood filmmakers displaced indigenous films and went on to achieve pop-cultural dominance.

The emergence of the home video industry in the early 1990s saw visionary filmmakers adopt familiar emotional codes, humour, melodrama, and everyday moral conflicts that audiences already recognised. They had an intimate view of Nigerian society, choosing not to be bystanders but catalysts, transforming viewers into participants with their familiar storylines and plots. This prioritised immediacy and relatability over prestige. Penetration before prestige.

Nollywood films embedded English within local rhythms, speech patterns, and social realities, helping the industry achieve street mass resonance and ultimately cultural domination.

The lesson for English-speaking rappers is to make their art intimate and relatable. Afrobeats artists do this excellently. Afrobeats superstars don’t become pop culture idols because of their technical skills and vocal prowess, but because of localised English speech patterns and subject matters intimate to the audience.

Which English-speaking Nigerian rapper will step up?

*If you enjoy The Naija Way, help us keep the stories coming — your support keeps the culture alive by donating HERE

It'll be a crime to drop heavy hitters like this and not have a PhD in Cultural Studies or something. Quite a thesis. 👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽

👍🏽👍🏽👍🏽