Chapter 1 - The Year of Death

1998 represents a key period for Nigerian politics, football and music. In this essay, I break down how a culture emerged from this volatile period.

“The Head of State, General Sani Abacha, is dead.”

1998 would be an important year in this thing of ours, Afrobeats. It is more than a genre. It is a lifestyle. It is a culture. It is the way we talk. It is the way we walk. It is music. It is dance. It is the way we love. It is Nollywood. It is even football. It is uniquely Nigerian.

Why 1998? This year, certain events that would shape the destiny of a generation occurred. These events would be the backdrop for a cultural renaissance by Gen X and millennial Nigerians.

I could choose any other point in our history, but this year allows for a neater and tighter contextual narration of who we are today.

My Afrobeats story starts on the evening of June 8, 1998. I was 14 years old. My siblings and I met our mum at home when we came from school. This was odd. Usually, we got home before our mum.

My mother worked at Mobil Oil Nigeria, one of the several oil companies in the country. While at work on this day, the Mobil staff got a security alert that something serious had happened in the country, and they needed to go home immediately. This was why we met her at home. The security alert did not disclose further details.

The weight of the security alert did not matter much to me. Nigeria was politically volatile in the 90s. I can't count the number of times my father took my siblings and me from school before closing time. These were the days of constant riots and protests in Lagos.

June 8 was going to be different. There was no power supply that evening, so I was on the balcony of our three-bedroom apartment in the LSDPC Residential Area in Oshodi for some fresh air. That's when the meteorite landed.

This was not a rock that fell from space and landed in Lagos. This meteorite shook the country. First, it came as a Yoruba gospel song, ‘Eru Olorun Bami’, by Dupe Olulana, released in 1993.

Our neighbour sang this song when she heard the news on the radio. The title means “I am afraid of the Lord.” In the following line, it says, “No one can stop what God has intended.”

This was the news - “The Head of State, General Sani Abacha, is dead.”

I stopped for a second when I heard this news. Then I jumped for joy in our living room. I was so happy that I stepped on a piece of nail. Thank God it wasn't rusty.

With adrenalin dulling the pain, I ran to the balcony and saw liberty and excitement rippling through the air. I saw people jumping, dancing and rejoicing on the street. The great dictator was dead. Praise the Lord!

General Sani Abacha passed after four brutal and tense years. His regime was a rule of tyranny and terror.

As a teenager, I consumed political news via my parents and other adults. The general feeling I got from them about Abacha was that he was a bad guy, a very bad guy.

Sani Abacha was born on September 20, 1943. He became a soldier in 1963, and his record shows he did not skip a single rank in his rise to general.

Three decades later, after joining the army, Abacha was one of the most powerful men in the country. From 1990 he was the Chief of Defence Staff and Minister of Defence. While he was a shadowy figure in the corridors of power, participating in coups, it was not until the events of June 12, 1993, that the tyrant would orchestrate his biggest coup yet.

His boss, Head of State Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, known by the acronym (IBB), or monikers ‘Evil Genius’ and ‘Maradona’, planned to hand over to a democratically elected government.

After a series of back-and-forth moves in our political Game of Thrones, June 12, 1993, was picked as the date for the presidential election.

The two candidates were business mogul Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola, the presidential candidate of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and another businessman Bashir Tofa of the National Republican Convention. He was from the North, while MKO was from the South-West.

The June 12 election would be one of the most significant moments in our history. MKO was ahead in the polls, an unpleasant surprise to the military ruling elite who preferred a Bashir Tofa presidency.

The Khaki boys had to do something. On June 24, 1993, IBB annulled the election results on the smoke screen grounds of vote buying and protecting the judiciary.

IBB “stepped aside” for an interim civil government on August 26, 1993. Chief Ernest Shonekan (a businessman from the South-West) led the interim government. His administration was a sitting duck for Abacha, who was still in the military. After only two months, Abacha forced the civilian government to step down in a palace coup.

Abacha's address to the nation on November 17, 1993, was a chilling declaration of power in an eerie monotone voice. It would set the tone of his regime.

The Abacha regime would be one of the darkest times of the Nigerian existence. His government did not tolerate opposition. He jailed MKO Abiola, former Head of State, Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, his deputy, Shehu Musa Yar'Adua and others who spoke against his dictatorship. Yar'Adua would die in detention years later.

A strike squad led by Sergeant Rogers orchestrated political drive-by killings, including MKO Abiola's second wife, Kudirat Abiola.

There was an attempt on the life of the founder and publisher of The Guardian (a Nigerian newspaper), Alex Ibru. A key political figure in the South-West, Pa Abraham Adesanya, miraculously survived an assassination attempt.

Abacha sentenced environmental activist Ken Saro Wiwa to death with the rest of the Ogoni 9, which triggered a series of sanctions from the international community. Political activists such as Wole Soyinka, Pa Anthony Enahoro and others flew out of the country to escape the bullets of the strike squad.

Two months before the death of the Rayban-rocking ruler, a military tribunal sentenced his deputy, Chief of General Staff, Lt. Gen. Oladipo Diya and five military officers to death, for planning an alleged coup.

Unlike IBB, Abacha had plans to transition to a civilian ruler like his Ghanaian counterpart, J.J Rawlings. He had already won the presidential ticket of four of the five political parties.

On March 3, 1998, a 2 Million March event for Abacha's election campaign took place, and it featured prominent Nigerians of the day from legendary singers, the hottest music acts of the day and members of the Super Eagles, Nigeria's senior male football team.

I stumbled on a clip of the event on YouTube, and it is bizarre, to say the least. In one of the videos, Nigerian football legend Segun Odegbami, British footballer of Nigerian origin John Fashanu, Super Eagle stars Uche Okechukwu, Austin ‘Jay-Jay’ Okocha and Daniel (The Bull) Amokachi were on stage. The Bull had close ties to the Abacha junta.

After listing Nigeria's sporting achievements under the Abacha regime, Fashanu predicted, “We are on course to win the World Cup.” This statement was met with loud cheers from the crowd.

I remember watching this event/concert on TV. I can only recall Sir Victor Uwaifo, the first Nigerian artist to earn the first gold record performing. He threw his guitar in the air. When he caught it, something was wrong with his guitar, and he had to switch it to another one. Maybe this was a signal that the whole vibe of the event was off.

Sir Victor Uwaifo performed his evergreen record ‘Joromi’, which rapper Cashman Davis had done a remix of during this period.

The whole affair seemed out of tune with what I heard my parents and other adults say about the state of the country at the time. The 2 Million Man March looked like the children of Israel worshipping Baal. I wondered why many eminent people showed up, but who says no to a dictator?

With no viable opposition, the Head of State's master plan to remain in Aso Rock was in its final stages when the unthinkable happened.

In the news footage on the government-owned, funded and controlled Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) that night, Abacha's corpse, wrapped in white fabric, was placed into a white van and driven out of the Aso Rock Villa to be buried in Kano. The troubler of Nigeria was no more.

“Eru olorun bami.”

General Sani Abacha 1943 - 1998

“It is unbelievable. He literally just came on the pitch.”

Twenty days after the death of General Sani Abacha, Nigeria's male national football team, the Super Eagles, faced Denmark in the second round of the 1998 World Cup in France.

Millions of Nigerians were anticipating an easy victory against Denmark. The real showdown was the possibility of a quarter-final match-up against the samba boys of Brazil in a rematch of the semi-final match of the Atlanta '96 Olympics.

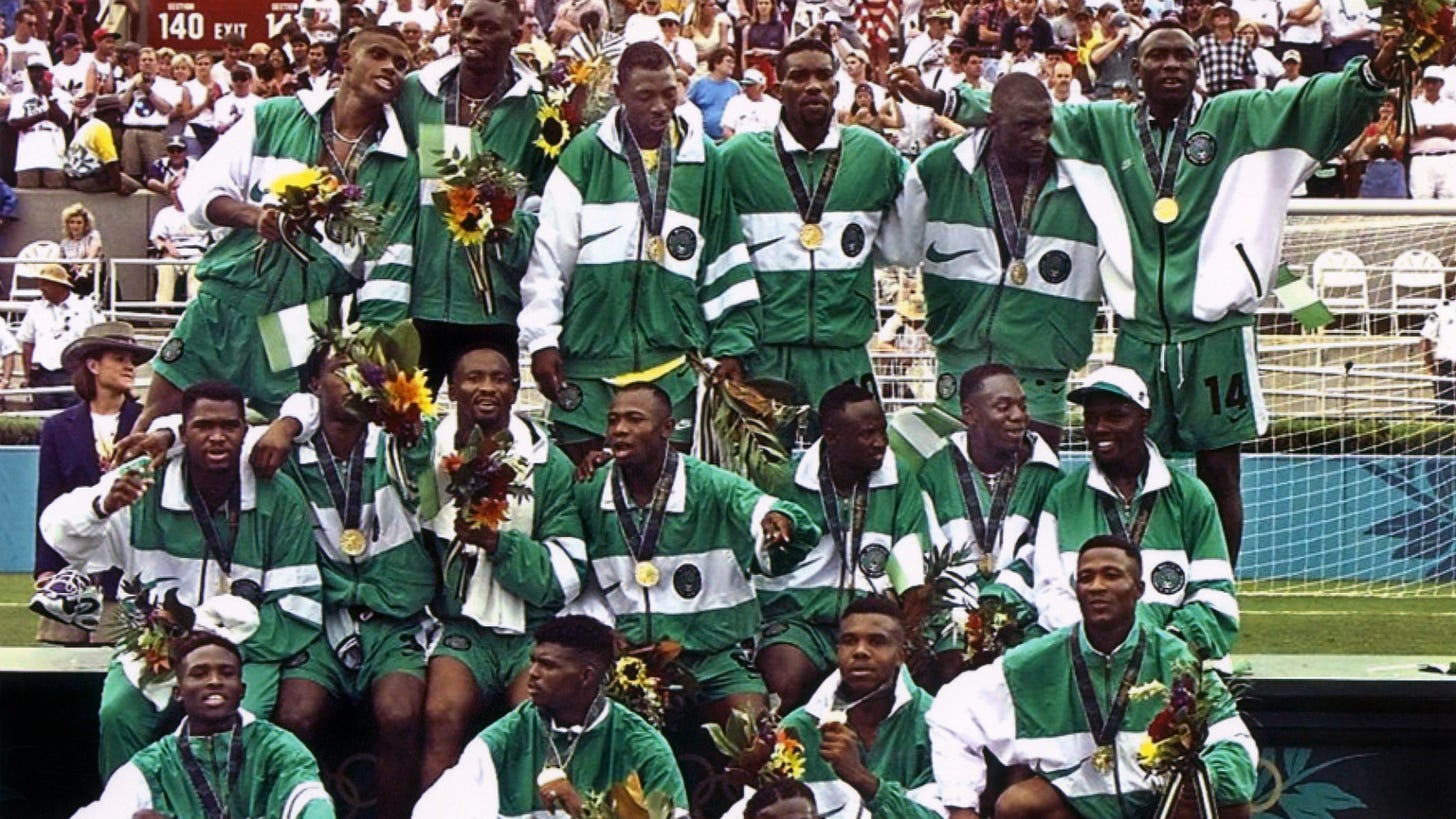

Our Olympic football squad, the Dream Team (because of the array of its football stars and a nod to the influence of American pop culture), defeated Brazil and Argentina in the semi-final and final to become the first black nation to win a football gold medal in the games.

In Nigeria's first match of the World Cup, the Super Eagles surprisingly defeated Spain in a five-goal thriller. Sunday Oliseh's rocket of a shot, Jay-Jay's bag of tricks that left his markers dizzy, and Garba Lawal's lucky shot made this a match to remember.

The second match was against Bulgaria. In USA '94, Nigeria crushed Bulgaria 3-0 in its first World Cup match. It was in this game Rashidi Yekini scored his only World Cup goal. His celebration is classified under the tag immortal. The goal machine poked his hands through the holes of the Bulgarian net, stretched his arms and uttered words that he took to his grave. This iconic celebration is one of the finest moments of undiluted Nigerian joy on the world stage.

The replay of this match four years later was a tight affair. Thanks to a lone goal by the Prince of Monaco, Victor Ikepba, the Eagles secured six points to qualify for the next round.

The team lost its final group match to Paraguay. Even though the game was a mere formality, the 3-1 defeat indicated that all was not well in the Super Eagles camp. Stories about indiscipline and a lack of focus followed the team to the World Cup. The Paraguay defeat clearly showed that there was serious trouble brewing.

The match against Denmark was at night. Three minutes into the game, the Danes struck. Denmark plucked green and white feathers with little resistance.

The Super Eagles conceded another goal nine minutes later. An embarrassing free-kick and failure to clear the rebound silenced a hopeful nation.

If a pin dropped in Lagos that night, a deaf man would have heard it. The Nigeria Football Supporters Club failed to sing on this night. Known for interpolating Gospel songs into football chants, the loud group of fans turned mute.

A glimmer of hope came before the end of the first half. Jay-Jay Okocha slipped a through ball to Nwankwo Kanu. The Big Dane, Peter Schmeichel of Manchester United, came out of his line to face Kanu one-on-one.

Two years ago, Kanu sold a marvellous dummy that swept Brazil's defenders away (including the swashbuckling Roberto Carlos) to score his most celebrated goal. This time, he could not move the Big Dane. He stuttered when it was time to pull the trigger. His lithe frame was far from its usual elegance and grace.

Kanu was a shadow of the flashy player he once was. The poster boy of Nigerian football was rusty.

Nwankwo Kanu was teammates with Taribo West at Inter Milan alongside the Phenomenon Ronaldo. Unlike West, his time in Inter Milan was a letdown.

After winning the Champions League with Ajax in 1994 and getting to the final the following season, Nwankwo Kanu went into the Olympics with the world at his feet. The lanky attacker with his signature devastating dummy lived up to the hype. He scored three goals in the tournament. Two of the goals came against Brazil in the semi-final. His performance in that game is unarguably the most iconic performance by a football player in a Nigerian jersey.

Unfortunately, dark clouds would hover over Kanu.

Inter Milan came for the prince of Nigerian football, and during his medicals, a cardiologist discovered he had a heart defect. Kanu underwent surgery to fix this.

Kanu found himself on the bench after his successful surgery. Going into the World Cup, he was out of form. His form was just one of the problems faced by the Super Eagles.

Legendary striker Rashidi Yekini was no longer the deadly poacher he was four years prior. He missed a beautiful chance in the match against Spain when Finidi George sent a sweet cross to him in the penalty box. Yekini jumped and hit the ball with a scissors kick, only for it to go wide. A few years ago, he would have buried that.

The Bull, Daniel Amokachi, suffered a knee injury going into the World Cup. The boisterous attacker's role was less impactful than it was in America four years ago, where he scored two goals.

The team's number-one goalkeeper didn't make the tournament. Ike Shorunmu had been in fine form for club and country until he broke his arm while playing for FC Zurich against GrassHopper before the World Cup. The veteran Peter Rufai, who was on holiday replaced him. Dodo Mayana's lack of preparation was glaring in the tournament.

The run-up to France '98 was awful. A 1-0 defeat to Germany, a 3-0 loss to Yugoslavia and a humiliating 5-1 spanking by Holland enraged passionate fans of the Super Eagles back home.

The politics of the Abacha regime also cut short the supremacy of the national football team in Africa.

Super Eagles did not defend the Africa Cup of Nations title it won in Tunisia in 1994 due to diplomatic issues between Nigeria and South Africa stemming from the execution of Ken Saro Wiwa by the Abacha regime. Coincidentally, the hosts, South Africa, won the tournament as the rainbow nation resurged from decades of apartheid.

CAF sanctioned Nigeria for withdrawing from the tournament and was not allowed to participate in the 1998 tournament.

Many Nigerians prayed for a miracle when the Super Eagles filed out for the second half of the match against Denmark.

There would be no Miracle of Dammam on this night. The Miracle of Dammam refers to the quarter-final match between Nigeria and the USSR at the 1989 FIFA World Youth Championship in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. The Flying Eagles of Nigeria came down from 4-0 to eventually win the match on penalties.

The Danes continued the onslaught in the second half. In the 58th minute, the Super Eagles collapsed when Ebbe Sand came in as a substitute.

Michael Laudrup waltzed past Oliseh, then flicked the ball over the head of Uche Okechukwu onto the path of Ebbe Sand. The Danish player sold a lovely dummy to the Super Eagles bogeyman Taribo West and smacked the ball beyond Peter Rufai. Ebbe Sand had only been on the pitch for 16 seconds.

The fourth and final goal for the Danes came in the 76th minute. The Super Eagles scored a consolation goal two minutes later, thanks to Tijani Babangida.

The golden generation of the Super Eagles ended on June 28, 1998, ten years after it got the nickname for its exploits at the 1988 African Cup of Nations (AFCON) despite losing to Cameroon in the final.

At AFCON 2000, co-hosted by Ghana and Nigeria, the Super Eagles would reach the final with many France '98 players.

Its loss to Cameroon (again!) in Lagos in the final was a ceremonial passing of the torch to its arch-rivals rather than a resurgence.

The Golden Generation of the Super Eagles 1988 -1998

“They just killed this man for nothing”

Abacha's death jolted the country. Football, the opium of the masses, had failed to produce the needed high.

It was a volatile time, but Nigerians were sure of one thing- democracy had to return. Nigerians were tired of military rule. It was time for them to go back to the barracks.

In the political world, the chess pieces had started moving. There was only one problem, Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola, winner of the June 12 presidential election, was alive and in detention. He was the elephant in the room.

Many of his supporters were dreaming of a Mandela-like exit from prison. Freedom started to look like a possibility for MKO Abiola when Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, visited the June 12 winner in detention.

According to the BBC, Annan announced on July 2, 1998, that the Federal Government would free him.

MKO Abiola was sceptical about his chances of becoming the president. He said it would be naive of him. Before delving into politics, the business magnate rubbed shoulders with the military boys. He knew how deadly things could turn.

While Nigeria anticipated the release of MKO, my brother and I focused on something else. We had forgotten about the loss of the Super Eagles. We were now rooting for the big teams in the World Cup.

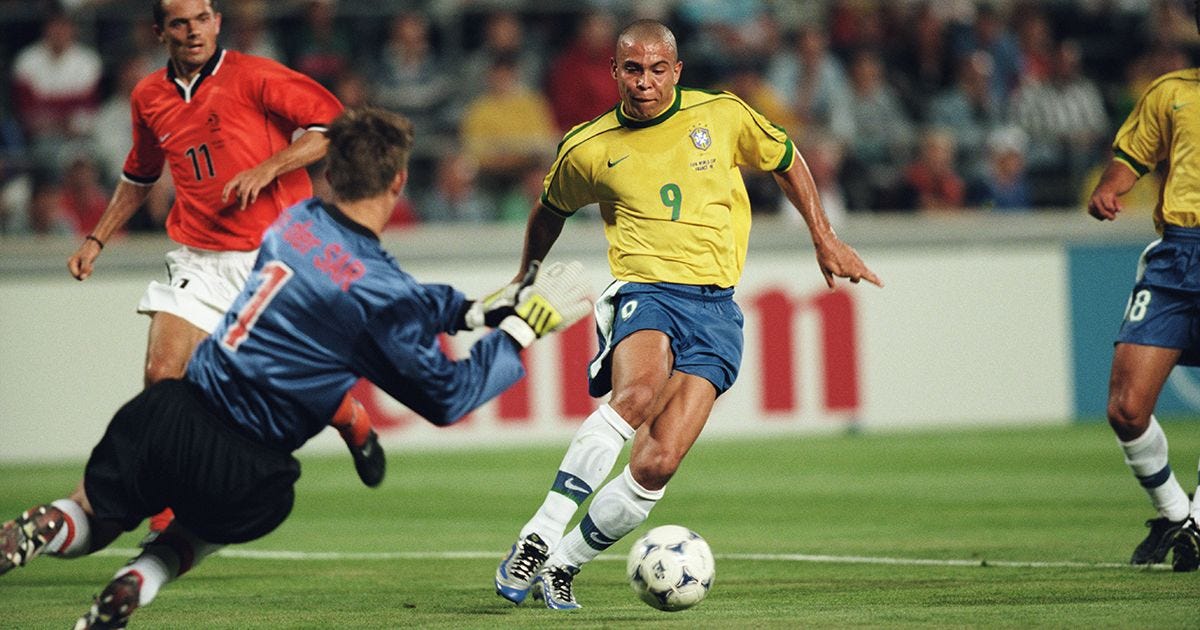

Brazil had expectedly advanced in the tournament and was about to face another fan favourite, Holland, in the semi-finals on July 7, 1998. The fixture boasted two lethal strikers- Ronaldo of the Selecao and Patrick Kluivert of the Oranje.

Ronaldo was the deadliest human being in world football. His stepovers, pace, and lethal shots had made him a goal-scoring machine and terminator of defenders.

At home, my brother and I played a game of headers that we developed. We would take turns at our makeshift post, the door beams at the entrance of the living room. When I was between the doorframe, my brother would throw a tennis ball against the wall on his right. The objective was to meet the ball with a glancing header and try to score. We took turns doing this, and whoever was the first to hit ten goals was the winner.

The glancing header was the trademark of Patrick Kluivert. The handsome flying Dutchman was ice cold when he struck the ball with his head. Whenever he jumped to meet a cross, time would freeze, keepers would be left paralyzed, and the ball would be at the back of the net.

There was ice in his veins.

I was in secondary school writing my Junior WAEC exam on the day of the clash between Holland and Brazil. My classmates and I couldn't stop talking about the showdown. Our excitement was punctured when one of our teachers told us there were rumours that MKO Abiola had died.

A few minutes later, my father showed up at my school. We had to get home quickly. The nation was on fire, and protests had begun to spread. It rained the day MKO died. On our way home, the Apapa-Oshodi expressway was black, with the stains of burnt tires lit by protesters. The clouds were grey.

At home, the Brazil and Netherlands match did not matter much. Kluivert missed a header in the first half. Ronaldo buried his chance in the second half by putting the ball in between the legs of Edwin Van Der Sar with his blue and metallic Nike Mercurial R9 boots.

Kluivert equalised with a thumping header as coolly as ever. The Netherlands lost to Brazil on penalties. During the match, my father angrily muttered, “They just killed this man for nothing.”

Chief MKO Abiola 1937 - 1998

“A time to be born and a time to die” - Ecclesiastes 3:2”

The deaths of MKO Abiola and Sani Abacha were a political reset button for Nigeria. A new beginning seemingly beckoned, and democracy would take us there - the promised land, Pax Nigeriana, or so we thought.

The eyes of the masses and the political elite were on the polling booth. Meanwhile, we, the kids, had our eyes on the television. Something else was on the horizon; something other than democracy was beckoning. The tectonic plates of culture were shifting slowly.

The pixels on the screen painted pictures of possibilities. Our minds were eager to escape the Nigerian contraption. TV was the escape. Radio too.

And in 1998, nothing was blasting louder in mass media than Hip-Hop music.

This African-American and Latino culture had taken over urban youth culture in Nigeria. The DJs on the radio played rap records all day. British TV series we grew up on like ‘Some Mothers Do ‘Av ‘Em’ and ‘Allo Allo’, had given way to ‘Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’ and other similar shows.

These black and brown youths from God’s country were ambitious, assertive, bold, creative and dominant. You could feel the sense of belief ripping through the songs. They were confident and determined to get the best of the societal traps laid before them by institutional racism.

Hip-Hop was more than aesthetics. Yes, we wore FUBU, sagged our pants and mimicked their accents, but Hip-Hop was inspirational also. A young generation would use the success of Hip-Hop as inspiration to beat the trap of being born in Nigeria.

Even as kids, we knew that the country was repressive and restrictive. We couldn't dream of a life beyond the borders of Nigeria. Only legendary Nigerian musicians of old, beauty queens and Nigerian football stars got international acclaim.

Chances were, if you were born local, you would die local unless you were lucky to win the US visa lottery as my uncle did. You either moved abroad or stayed in Nigeria and lived a life of 'what if'. There was no middle life. You couldn't conquer the world from Lagos, Kano or Enugu.

Then came Hip-Hop, and we saw young men and women in our colour kick ass and take over the world.

Radio and TV were the main drivers of culture in 1998, and two young men in an obscure part of Lagos called ‘Alagbado’, would push the faders and turn the knobs that would start the story of a generation's rise to global recognition and fame.

A business magnate Chief Raymond Anthony Aleogho Dokpesi, a friend of MKO Abiola, established his radio station Raypower in 1994 after the deregulation of the broadcast sector in 1992.

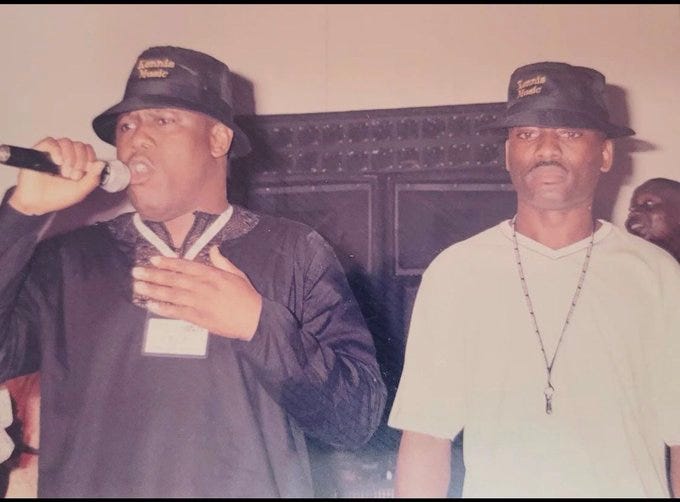

Dokpesi hired two young men Kehinde ‘Kenny/Keke’ Ogungbe and Dayo 'D1' Adeneye, who had just returned from America. Kenny and D1 played a significant role in making the radio station the hottest thing on the streets of Lagos.

They not only played the latest rap and R&B hit singles, but they also jammed it. The two best friends referred to it as “jamming the Jamz.”

Their American sensibilities would prove pivotal to establishing themselves as the new tastemakers. Apart from jamming the latest American jamz, they had a bias for local talent. Raypower became a platform to help emerging local acts gain airplay in the lucrative Lagos market. One of them was Daddy Showkey, an energetic singer and dancer that ushered the ‘galala’ movement in Nigeria and made Ajegunle, the hotbed of music in the mid-90s. Daddy Showkey is the earliest prototype of GRAMMY-winning Burna Boy.

In 1998, Keke and D1 established the seminal music label Kennis Music. In the same year, they also created their show AIT Jamz.

The show aired every Friday night on Dokpesi's TV station, Africa Independent Television (AIT).

Circa 1997, Keke and D1 signed the group Remedies. Rapper Eedris Abdulkareem and singer Eddie Montana initially made up the group. Tony Tetuila would join them later. The group's first single ‘Shako Mo’ came out in 1998, including the video.

In the year of death, life was born into a generation. The first few seconds of ‘Shako Mo’ sounds like the break of dawn. It sounds like a new day.

When the vocalist Eddie Montana wails, it feels like a symbolic call to his generation that the time is now. We are the ones we have been waiting for. No political messiah was going to save us. We would have to do this ourselves. We would draw the blueprint and create an empire that would reach the farthest ends of the universe.

The title of the single, which is in Yoruba, roughly means “I am no longer proud.” Pride is one of the seven sins. James 4:6 says “God opposes the proud but gives grace to the humble.” This generation would be humble enough to do the heavy lifting required to activate Nigeria’s music industry which collapsed for much of two decades. This generation started from nothing and had the talent and grace to build the music scene brick by brick.

The 'Shakomo' instrumental is a sample of MC Lyte's 'Keep On, Keepin' On' featuring Xscape in 1996, which also samples Michael Jackson's 'Liberian Girl'. On ‘Shako Mo’, traditional Yoruba drums punctuate the Hip-Hop instrumental, which gives it a Nigerian twist. Think Hip-Hop with a Nigerian flavour. The early strain of Afrobeats was a mutation of the Hip-Hop sound.

Rapper Eedris switches from English, Yoruba, and Hausa while employing a simplistic rhyme pattern. At some point, it is playful. Eddie Montana takes a rap-sung approach and also keeps it simple. Today, Eddie Montana's lines would be considered rap in this melody-intensive climate.

The visuals of ‘Shako Mo’ start on an underwhelming note. We see the trio at the beach - a location over-flogged by Nigerian music video directors and movie directors at the time.

The Remedies wear French Safari suits with African prints. The video vixens also wear dresses with African prints. Nothing in the first few seconds of this video would make you believe that you were about to witness history.

At one point, one of the Remedies falls on the sand comically. It feels like a cheesy Nollywood love scene. However, when Eddie Montana starts to wail, the three group members slowly fade into the picture.

In a new scene, Eedris, Eddie and Tony wear three white T-shirts. The scene after this sees them performing in a dark, smoky nightclub. These cuts are quick, but they are enough to grab your attention.

Eedris Abdulkareem is the star of the show. His presence is magnetic. At some point in the video, he goes topless, showing us his cut physique and virility.

When Eedris begins to rap, he is in the centre of a house party. On the surface, the ‘Shako Mo’ video looks like a cheap imitation of the Hip-Hop videos we saw on AIT Jamz.

On the flip side, the raw quality of it made it so familiar and intimate. It struck an immediate chord with a generation itching for freedom and expression in a society with little structure or form.

The video reflected the youth culture of the time, a thirst for Hip-Hop fashion brands and a hunger to get into the most exclusive house parties.

Yes, you could step into the hottest parties, but how you showed up also mattered. Did you show up rocking FUBU, Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klien, and Nautica? These were the top designer brands at the time.

Tony Tetuila rocks a Mecca shirt in the video. Eddie Montana wears a Tommy Hilfiger long sleeve polo shirt as he and his friends walk in a plaza as if they own the place. Eedris's shirt has the number 9 written on its back, like a striker’s jersey.

The Remedies imposed Nigerian consciousness on an American expression. The members of the Remedies took the familiar, flipped it and made it overtly intimate.

A fallen dictator, a dead business tycoon turned politician, and a national football team that had its wings plucked on the world stage took the headlines in 1998.

In the background, three young men were laying an intrinsic formula of the Afrobeats sound.

There is something prophetic about ‘Shako Mo’ that many have not picked out. In the hook, we can hear Africa mentioned. Towards the end of the record, Eedris Abdukareem name-drops America and London - two geographical spots that would help Afrobeats blow up outside the continent.

Did The Remedies know Afrobeats would dominate Africa and the world? Maybe Eedris knew this song would light the fuse that would lead to the explosion of Afrobeats in Western Europe and North America. Maybe, he didn't know. It could have been a coincidence.

One thing is sure the time had come for a new generation to sing its songs.

Afrobeats 1998 - Till Infinity

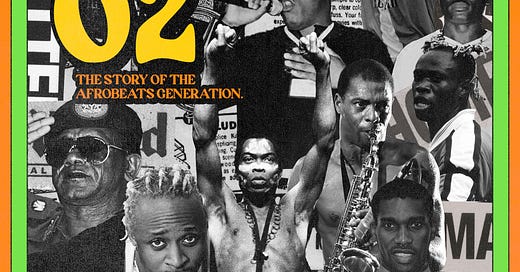

This is an excerpt from Chapter 1 of my book ‘From Ojuelegba to O2’ - The Story of the Afrobeats Generation. It will be released in 2024.

This was such an amazing and insightful read. As someone who has always looked for books on the history of Nigerian music, I'm happy about this documentation. Looking forward to reading the book

I can’t wait to read the book ! I was born in 95’ and while I was still a baby when a lot of these events happened they were the backdrop and my childhood and definitely shaped who I am today. and I am so happy our history and culture is being documented so beautifully by amazing people like you.

As an architect one of my dreams is to play my role in curating and elevating our rich vibrant culture and spreading it to the world through architecture and the built environment. Thank you for the inspiration AOT 🙌🏿🙌🏿